Career Development and the 18-Month Cliff

Your finance team calculates employee productivity curves. Onboarding takes three months. Full productivity arrives around month six. Peak efficiency? Months twelve through twenty-four, when institutional knowledge meets skill mastery. This is when employees deliver maximum value relative to compensation.

This is also precisely when they leave.

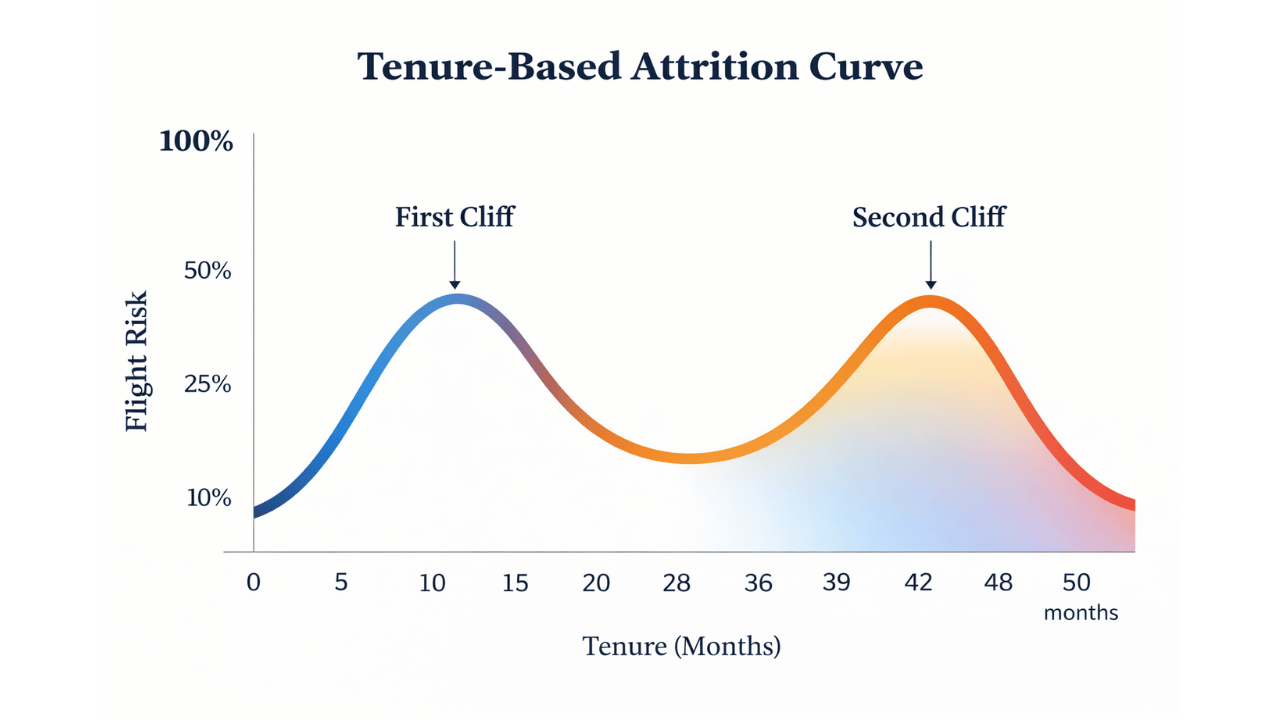

The data reveals a pattern most executives miss: employee attrition follows predictable tenure curves, with pronounced peaks at eighteen months and three to four years. Research across industries shows the first spike occurs just as employees transition from learning to contributing, right when your training investment begins paying dividends. The second arrives when they've mastered their role but see no clear path forward.

The timing is economically irrational. You invest twelve to eighteen months developing an employee. They reach full productivity. Then they leave because they cannot see year three. You've funded their training for their next employer.

The Tenure Risk Curve

Employee flight risk is not constant; it follows a predictable J-curve based on tenure. The pattern appears across industries, though timing varies by sector and role complexity.

Months 0-6: The Honeymoon

Attrition during onboarding is typically low. New employees are learning systems, building relationships, and experiencing the initial excitement of a new role. The switching costs are high; they just left another job, explained their decision to family and friends, and endured the disruption of transition. Leaving now means admitting a mistake and restarting the search process.

The retention risk here is real but different: poor onboarding drives early departures. Employees who struggle to integrate or achieve quick wins may cut losses early. But most who survive the first six months stay through month eighteen.

Months 6-18: The Danger Zone Approaches

This is the skill-building phase. Employees gain proficiency, contribute meaningfully, and integrate into teams. Productivity rises while compensation remains relatively flat - the period of maximum ROI for employers.

But around month twelve, a psychological shift begins. Initial excitement fades. The role's challenges become routine. And critically, employees start asking: "What's next?"

Month 18: The First Cliff

Research suggests attrition risk peaks around eighteen months of tenure. The reasons converge:

Career path clarity evaporates. During interviewing, companies describe growth opportunities. During the first year, employees are too focused on learning to care. By month eighteen, they expect to see that promised path materialize. If it doesn't, if the route to promotion is unclear or blocked, they start looking.

Marketability reaches maximum. Eighteen months of experience reduces job-hopper concerns enough to make external searching feasible, though some stigma remains. Recruiters will engage. Former colleagues ask if they're happy. The external opportunity set expands just as internal advancement appears limited. Many employees begin exploratory conversations even if they're not actively interviewing yet.

The excitement-to-effort ratio inverts. Early tenure offers novelty and learning. By month eighteen, employees know the systems, the people, and the work. If the role hasn't expanded in scope or complexity, routine replaces challenge. The effort required stays constant while the psychological reward diminishes.

Training investment is complete. Employees have absorbed institutional knowledge and built necessary skills. They're productive contributors who no longer require oversight. They're also highly attractive to competitors who can capture that value without paying the training cost.

The eighteen-month mark represents maximum vulnerability: high marketability, unclear internal path, reduced novelty, and complete portability of skills.

Years 2-3: Temporary Stability

Employees who navigate the eighteen-month cliff often stabilize temporarily. Perhaps they received a promotion, expanded scope, or adjusted expectations. But the stability has another driver: many who started exploring at eighteen months wait until crossing the two-year threshold before intensifying their search. At two years, job-hopper stigma fades significantly. By year three, it disappears entirely.

This period appears stable from retention metrics, but it's often a holding pattern. Employees who felt uncertain about their path at eighteen months haven't forgotten; they're waiting for resume safety before making their move.

The clock is ticking.

Years 3-4: The Second Cliff

The second attrition spike arrives when employees have truly mastered their role. They can perform core responsibilities efficiently, anticipate challenges, and operate with minimal supervision. This is peak productivity.

It's also peak boredom.

Research on employee engagement shows a clear pattern: job satisfaction rises during the learning phase, plateaus during proficiency, and declines during mastery without advancement. At three to four years, employees face a critical decision point:

Role mastery without growth equals stagnation. The challenges that engaged them in year one are now routine. They've built the systems, improved the processes, and achieved the wins. What's left? Repeating the same cycle.

External opportunities multiply. Three to four years of experience positions employees as experienced professionals, not junior contributors. They're attractive to competitors seeking proven performers. Recruiters actively pursue them. Former colleagues who left have landed at other companies and make introductions.

Internal advancement appears blocked. The organizational pyramid narrows. There are fewer manager roles than senior individual contributors. Promotion cycles slow. Employees see colleagues who've been "ready for promotion" waiting two to three years. The math becomes clear: staying means waiting, potentially indefinitely.

Compensation growth stalls. Early tenure often brings annual raises as employees gain proficiency. But once they reach full productivity, raises shrink to cost-of-living adjustments. The only path to meaningful compensation increases is promotion, which appears blocked, or external offers.

The three-to-four-year mark represents a different kind of cliff: employees have given you their growth phase and received diminishing returns. They've proven their value. Now they're deciding whether to wait for internal advancement or capture their market value elsewhere.

What Employees Need at Each Stage

Employee development needs follow the tenure curve. Companies that match development investment to these needs retain talent. Those that don't face the cliffs.

Months 0-6: Onboarding and Quick Wins

New employees need successful integration and early visible achievements. This isn't about development; it's about not eliminating them before they start.

What works: Clear onboarding processes, early project wins, manager check-ins, peer relationships. Investment here prevents early attrition but doesn't address the eighteen-month cliff.

What fails: Sink-or-swim cultures, absent managers, unclear expectations, isolation from teams.

Months 6-18: Skill Building and Integration

Employees are learning rapidly and building capabilities. They need skill development, increasing responsibility, and integration into meaningful work.

What works: Training programs, stretch assignments, expanding project scope, mentorship, technical skill development. This phase builds competence and engagement.

What fails: Stagnant responsibilities, no learning opportunities, routine task assignment without growth.

Months 18-36: THE CRITICAL WINDOW

This is where most companies fail. Employees need to see a clear path forward, either through promotion, scope expansion, or lateral skill development. Without it, they leave.

What works:

Clear promotion criteria and realistic timelines. Not vague promises but specific requirements: "Promotion to Senior Analyst requires X, Y, Z achievements, typically reached in 18-24 months." Transparency removes ambiguity.

Scope expansion without title change. If promotion slots are limited, expand responsibilities. Lead projects. Mentor junior employees. Own broader initiatives. Scope expansion provides growth even when titles can't change.

Lateral skill development. Create opportunities to build complementary skills. An engineer might lead customer implementations. An analyst might present to executives. Cross-functional exposure builds capabilities and engagement.

Explicit career conversations. This is probably the most important. Don’t assume everyone wants the same things. Don't wait for annual reviews. Discuss career development quarterly. Ask: "What skills do you want to build? What does your ideal role in two years look like? How can we create that path here?"

What fails:

Annual review cycles. Waiting twelve months to discuss career development is far too slow. By the time the review arrives, high performers have already started looking.

Vague promises. "Keep doing great work and opportunities will come" offers no timeline, no criteria, and no commitment. Ambitious employees hear: "We haven't thought about your career path."

Promotion bottlenecks without alternatives. If there are five senior ICs and one manager role, four people face a blocked path. Without lateral options or scope expansion, they leave.

Years 3-5: New Challenges or Stagnation

Employees at this tenure need fundamentally different challenges or they disengage. The development playbook from years one and two no longer works - they've built those skills.

What works:

Major scope increase. Lead new initiatives. Own strategic projects. Take on direct reports (if management track). The challenge must match their expanded capabilities.

Lateral moves to different functions. An experienced analyst moving into strategy. An engineer transitioning to product. Cross-functional moves provide novelty while retaining institutional knowledge.

Leadership opportunities without management titles. Lead projects, mentor teams, represent the company externally, influence strategy. Many high performers want impact without direct reports.

Strategic involvement. Include them in decision-making, planning, and direction-setting. Experienced employees disengage when excluded from strategic conversations.

What fails:

More of the same. Expecting employees to repeat year three indefinitely. Mastery without new challenges breeds departure.

Default to management track. Not every high performer wants to manage people. Forcing technical experts into management (or offering no alternative) drives attrition.

Ignoring market realities. At three to four years, employees know their market value. If internal compensation and opportunity lag external options significantly, they leave.

Why Companies Fail at Development

The development failure is not mysterious. Companies face structural barriers and behavioral blind spots that prevent effective career development.

No Clear Paths Beyond Senior IC Roles

Most organizations have defined paths to senior individual contributor, then... nothing. The only advancement option is management, which has limited slots and doesn't suit everyone. Companies create dead-end roles, then wonder why people leave.

The alternative, dual IC/management tracks with equivalent prestige and compensation, exists in some tech companies and consulting firms. But most organizations still default to "up or out," where "up" means management.

Promotion Bottlenecks Create Quality Inversion

When promotion slots are limited and progression is slow, the best employees leave first. They have the most options and the least tolerance for waiting. Average performers stay; they face less certain external opportunities.

This creates a quality inversion: your retention efforts keep people who have fewer alternatives while losing people with the most potential.

Managers Don't Discuss Career Development Proactively

Most career conversations happen during annual reviews, initiated by HR requirements, not ongoing manager engagement. By then it's too late; high performers have already begun interviewing.

The failure is behavioral. Managers know they should discuss development but:

They're busy and deprioritize career conversations

They lack training on how to have these discussions effectively

They worry that discussing career path will encourage departures

They have no budget or authority to promise promotions

So they default to vague encouragement and hope employees stay satisfied.

Development Requires Coordination Companies Don't Have

Effective career development needs:

Cross-functional visibility into opportunities

Budget flexibility for lateral moves and training

Manager willingness to let high performers transfer

HR systems that track development plans and progress

Leadership commitment to creating diverse paths

Most companies lack these coordination mechanisms. Career development becomes each manager's isolated responsibility, with predictable results.

Annual Cycles Are Too Slow

Career development happens in annual review cycles. Compensation adjustments happen annually. Promotion decisions happen annually. Meanwhile, employees' career needs and external opportunities operate continuously.

By the time your annual review cycle identifies a flight risk, they've already interviewed elsewhere and received offers. Annual rhythms guarantee reactive responses to continuous dynamics.

The Development Investment Economics

Finance teams evaluate retention strategies through cost-benefit analysis. Career development investments compete with retention bonuses, compensation increases, and other tools. The question: what's the ROI?

Development Investment Costs

Time commitment: Manager time for career conversations (2-4 hours quarterly), mentorship programs, training programs. Estimate $5,000-10,000 annually per employee in time costs.

Program costs: External training, conferences, certification programs. Highly variable, from $2,000 (online courses) to $20,000+ (executive programs). Most effective development happens through expanded scope and project assignments, which cost primarily in manager time and coordination.

Opportunity cost: Promoting or expanding scope for one employee may delay opportunities for others. This is real but hard to quantify, and less costly than losing the employee entirely.

Total development investment: approximately $10,000-25,000 per employee annually for meaningful career development, heavily weighted toward manager time and training programs.

Replacement Costs

Contrast this with replacement costs when employees leave:

Direct recruiting costs: External recruiter fees (20-30% of salary), job board postings, interview time. For a $100,000 employee: $20,000-30,000.

Productivity loss during vacancy: 3-6 months to fill role, during which work is delayed, distributed to others, or simply not done. For a high-performing employee: $25,000-50,000 in lost output.

Onboarding and training: 3-6 months for new employee to reach full productivity. During this period they consume manager time and peer support while producing limited output. Cost: $30,000-50,000.

Institutional knowledge loss: The departing employee takes knowledge of systems, customers, internal relationships, and processes. This information takes months to rebuild. Difficult to quantify but material, estimate $10,000-20,000 in reduced efficiency and repeated mistakes.

Team disruption: Remaining employees absorb extra work, experience morale impact, and in some cases begin their own job searches. When one employee leaves, attrition risk rises for peers. Cost: variable but significant.

Total replacement cost: $85,000-150,000 for a $100,000 employee, or 85-150% of annual salary.

The ROI Calculation

Development investment: $10,000-25,000 per employee annually

Replacement cost avoided: $85,000-150,000 per departure prevented

If effective career development reduces attrition from, say, 20% to 10% in a 100-person division:

Prevented departures: 10 employees

Replacement costs avoided: $850,000-$1,500,000

Development investment: $1,000,000-$2,500,000 for all 100 employees

The math appears close, even unfavorable. But the calculation misses several factors:

Targeted investment: Development doesn't require equal investment across all employees. High performers and flight risks (those at eighteen months or three to four years) warrant more investment. Average performers and recent hires need less.

If you concentrate development investment on the 30% of employees at highest flight risk:

Development investment: $300,000-$750,000

Replacement costs avoided: $850,000-$1,500,000

Now the ROI is clearly positive, even before considering quality effects.

Quality compounding: Preventing departures of high performers has multiplier effects. These employees mentor others, drive important projects, and attract talent. Losing them damages team capability beyond the individual's output. Retaining them compounds value over time.

Recruitment difficulty: The replacement cost assumes you can find equivalent talent. For specialized roles or tight labor markets, replacement may be impossible at market rates. Development investment looks far more attractive when external hiring is constrained.

The fundamental economics favor development investment, especially when targeted at high performers during critical tenure windows. The ROI improves further when considering that development creates value even for employees who stay - expanded capabilities benefit the organization regardless of attrition.

The Framework: Tenure-Based Development Strategy

Finance-minded retention strategy matches development investment to tenure-based flight risk.

Segment employees by tenure and performance:

Months 0-18, high performers: Low immediate flight risk but approaching the eighteen-month cliff.

Investment: manager career conversations starting at month twelve, skill development opportunities, clear promotion criteria communication.

Months 18-36, high performers: MAXIMUM FLIGHT RISK.

Investment: explicit career pathing, scope expansion, promotion if warranted, lateral development opportunities. This segment warrants highest per-capita development spend.

Years 3-4, high performers: Second cliff approaching.

Investment: major scope changes, strategic involvement, leadership opportunities, or promotion to next level. If no clear path exists internally, these employees will leave.

Average performers, all tenures:

Moderate development investment focused on maintaining competency and engagement. Not every employee warrants intensive career development; concentrate resources on high performers who drive disproportionate value.

Low performers, all tenures:

Minimal development investment. If they're not meeting performance standards, development won't drive retention; capability gaps or motivation issues prevent success. Address performance directly or exit them.

Implement tenure-triggered interventions:

Month 12: Manager initiates first formal career development conversation. Discuss employee's two-year vision, required skills, potential paths. Document and revisit quarterly.

Month 18: Executive or senior leader meets with high performers for career discussion. Signal that leadership is aware of their contributions and invested in their growth. Provide concrete development plan with six and twelve-month milestones.

Month 24: Evaluate progress against development plan. If promotion is warranted, execute. If not yet ready, provide specific gap analysis and timeline. If path is blocked, offer lateral moves or scope expansion.

Year 3: Major scope evaluation. Can you provide fundamentally new challenges? If yes, implement. If no, be honest about limitations and prepare for potential departure.

Create structural support:

Dual IC/management tracks: Provide advancement paths for high-performing individual contributors who don't want to manage people. Equivalent compensation and prestige.

Lateral movement programs: Enable cross-functional transfers without penalty. Make internal mobility easier than external job searches.

Manager training on career development: Most managers have never been trained to discuss career pathing effectively. Provide frameworks and coaching.

Transparent promotion criteria: Publish what's required for advancement. Remove ambiguity that drives employees to external searches for clarity.

Quarterly career check-ins: Don't wait for annual reviews. Brief, regular conversations keep development on track and signal investment.

When Development Investment Doesn't Make Sense

Career development is not always the optimal retention strategy. Sometimes attrition is beneficial.

Let low performers leave: Development investment in employees who aren't meeting expectations is often wasted. Address performance directly or accept their departure. Resources spent retaining low performers could develop high performers instead.

Accept attrition in high-turnover roles by design: Call centers, retail, seasonal work - these roles have inherent attrition due to compensation levels, work nature, or employee life stage. Fighting this with development investment yields poor ROI. Design for turnover instead.

Don't over-invest in retention-proof roles: Some employees will leave regardless - relocating spouses, career changes, returning to school. Recognize when external factors dominate and development won't change outcomes.

Know when the path genuinely doesn't exist: If you're a 20-person company with one senior engineer role and three engineers who want it, someone will leave. Sometimes the honest conversation is: "I can't create three senior positions. I value your work, but I understand if you need to find growth elsewhere." Candor beats false promises.

The optimal development strategy is targeted: intensive investment in high performers during critical tenure windows, moderate investment in solid contributors, minimal investment in low performers or roles with structural attrition.

The Eighteen-Month Cliff Is a Choice

Employee attrition follows predictable patterns. The tenure curve is not mysterious; research has documented it, executives have observed it, and finance teams have calculated its cost. The eighteen-month and three-to-four-year cliffs appear reliably.

What's less predictable is whether companies will respond.

Most don't. They invest twelve to eighteen months training employees, watch them reach peak productivity, then lose them because no one discussed career development. The replacement cycle begins, consuming 85-150% of salary to find someone new to train for eighteen months before losing them.

The alternative is straightforward: match development investment to tenure-based flight risk. Have career conversations before employees start searching. Create paths that employees can see, with clear criteria and realistic timelines. Expand scope when promotions are blocked. Offer lateral development when vertical advancement is limited.

The economics favor development. The ROI is measurable. The interventions are known.

The question is whether leadership will implement them, or continue funding departures with training budgets.